Article published by the Gatestone Institute, 2 May 2021. © Richard Kemp

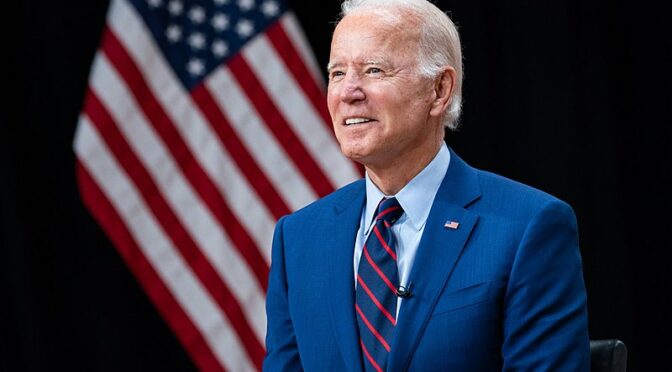

US President Joe Biden’s unconditional withdrawal of US forces from Afghanistan by September this year has potentially grave and dangerous consequences far wider than that embattled country and is set to undermine the national security strategy he proudly unveiled only days before announcing his pull-out.

In 1982, Admiral Sir Henry Leach, head of the Royal Navy, told Margaret Thatcher that if Britain didn’t retake the Falkland Islands when Argentina invaded, ‘in another few months we shall be living in another country whose word counts for little’. He knew that failure to resist a dictator who seized sovereign territory by force would be a green light to such aggression everywhere. The same calculation underpinned President George H. W. Bush’s decision to unleash one of the most powerful armies in history following Saddam Hussein’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

Far worse than failing to intervene is intervening to fail. The withdrawal from Afghanistan is just that. Biden did not order US forces there in 2001, but as Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee at the time, he strongly supported it. Later he said: ‘History will judge us harshly if we allow the hope of a liberated Afghanistan to evaporate because we failed to stay the course.’

It will not be history alone that judges Biden’s failure to stay the course now, but America’s allies, enemies and competitors around the world. His March 2021 National Security Strategic Guidance says:

‘Authoritarianism is on the global march, and we must join with likeminded allies and partners to revitalize democracy the world over. We will work alongside fellow democracies across the globe to deter and defend against aggression from hostile adversaries. We will stand with our allies and partners to combat new threats aimed at our democracies.’

Biden emphasises the need to work with NATO and other allies, which he describes as ‘America’s greatest strategic asset’.

Fine words butter no parsnips, as Harry Truman was fond of saying. Biden’s unconditional withdrawal from Afghanistan provoked the first public statement of dissent against US security policy that I can recall in my lifetime from Britain, America’s closest military ally and NATO’s next most powerful member. Prior to Biden’s decision, both France and Germany, which is the second largest troop contributor behind the US, also opposed withdrawal in the current circumstances, and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg echoed their views.

US allies who have themselves invested huge military and economic resources in Afghanistan fear a Taliban return to power and the blood-bath that would likely accompany it. Their concerns are shared by General Kenneth McKenzie, commander of US CENTCOM, responsible for Afghanistan, who told the Senate Armed Services Committee last week that Afghanistan’s forces might well collapse following US withdrawal.

America’s partners are fearful also of an intensified threat from global jihadists. Al Qaida — along with Islamic State-Khorasan, with which it sometimes collaborates — would regain their preferred base for attack against the West. As before, Western citizens would flock to Afghanistan for terrorist training. Jihadists everywhere would be encouraged and empowered by a perceived US defeat at the hands of the Taliban, which was being trumpeted by Al Qaida within days of Biden’s announcement.

Biden justified his withdrawal with the need to counter challenges from China and Russia and strengthen democratic allies and partners against autocracy. His actions are likely to have the reverse effect.

The abandonment of Afghanistan will long be remembered by countries around the world as they weigh their choices between the US and authoritarian regimes. Already Saudi Arabia has recognised that Biden will not protect them from Iran, with his administration rushing headlong to rejoin the catastrophic nuclear deal and withdrawing support to the Kingdom in its fight against Iranian proxies in Yemen. Fearful for their future, the Saudis know they cannot stand alone against Iran and have opened talks with Tehran, a move that could only harm US interests in the region.

Across the Pacific, Taiwan is increasingly plagued by Chinese bomber incursions into its airspace, at greater intensity since Biden took office. Chinese President Xi Jinping says Taiwan must and will be ‘unified’ with China, by force if necessary. How confident can Taiwan now be that the US will actively help them resist should China invade? More importantly, Xi will be asking the same question while he counts the potential cost of moving against the country that he considers his own.

As Russian forces massed along the border with Ukraine last month, Xi will also have noticed that Biden cancelled a transit of the Black Sea by two US warships after Russia told Washington to stay away, calling its planned naval deployment an unfriendly provocation.

Like a kettle of vultures, Pakistan, Iran, China and Russia will all be circling the Afghan carcass following US withdrawal. Iran, which has long provided weapons, funding and safe haven to the Taliban, has been building its influence with them in recent months. Russia has also helped fund and arm the Taliban — sometimes in collaboration with Iran — to kill Afghan, US and NATO forces in order to challenge the US and increase its own influence in the country. China too has been cooperating with the Taliban, both to hunt down and kill Uighur Muslim leaders and in its hunger for natural resources. It also sees influence in Afghanistan as a means to confront New Delhi. Beijing knows that India, as a US ally and democracy, is the only regional power that could play a genuinely constructive role in a future Afghanistan. Xi is not willing to see that happen.

Pakistan, in cahoots with China, is also determined to keep India out of Afghanistan. Its Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate created the Taliban and today remains by far the greatest external backer of its campaign against Afghan and international forces. Islamabad sees the country as vital strategic depth in a future conflict with India and intends to hold sway over a future Taliban regime in Kabul. But it might have to pay a severe price it did not anticipate as it recklessly fuelled the conflict: a flood of Afghan refugees fleeing the Taliban onslaught. They would join the vast number already there, which Islamabad struggles to support. By the end of 2001, 4 million Afghan refugees were in Pakistan, with 1.4 million still there today. This will not be a problem for Pakistan alone; Iran, Turkey and Europe may also face a huge additional influx. Even before Biden’s withdrawal, Afghans are already the second largest migrant population in the world.

There is also the prospect of instability in Afghanistan flowing across the border and further destabilising Pakistan with potentially devastating strategic consequences. Intent on overthrowing the government — with its nuclear armory — Jihadists there have been butchering mercilessly for years. Taliban success next door would embolden them and potentially provide support. The soon-to-be-ended US presence in Afghanistan has helped suppress the insurgency in Pakistan. There are suggestions that US assets deployed in Pakistan might have the same effect in Afghanistan, but that is at best questionable, even if Islamabad allows it.

All of this is a high price to pay for ending what Biden calls the ‘forever war’ in Afghanistan. The truth is this is a forever war for the US only in the rhetoric of those who support surrender to the Taliban. Afghan troops continue to suffer horrific levels of attrition, but the last US combat death there was over a year ago. If a conflict needs to be fought in the first place, it may require an enduring presence, sometimes for decades — look for example at US forces still deployed today in South Korea, Germany and Japan. Look also at the consequences of Barack Obama’s precipitate withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 — the rise of the Islamic State and the costly return of US forces for almost another decade and counting.

There are just 3,500 US forces (including off-the-books units) among the 10,000 NATO and other international troops in Afghanistan, all of whom are dependent on US presence. Their function is not combat but training and assistance to Afghan security forces. The US also conducts counter-terrorist operations using intelligence agencies, special operations forces and air assets, the very approach Biden unsuccessfully argued for when vice president, as he opposed the more extensive counter-insurgency campaign that Obama prosecuted while in office.

The net strategic effect of Biden’s unconditional withdrawal is shaping up to be the opposite of what his national security strategy seeks to achieve: diminished confidence among allies, increased boldness among adversaries, the vital strategic territory of Afghanistan ceded to anti-democratic autocracies, a destabilised region containing two nuclear powers with associated proliferation risks, a spiralling of the global jihadist threat and massive population displacement.

Image: Wikimedia Commons