In wartime, serving men want to be with their comrades. It’s those at home who suffer the real pain of absence

Originally published in The Times, 24 December 2010. © Richard Kemp

As the recently released and much acclaimed film The King’s Speech shows, oratory did not come easily to George VI. But fighting to overcome his nervous stammer, he became an inspirational symbol of this country’s resistance to the Nazi menace. The King’s leadership was never more vital than in the dark days of 1940. That year the theme of his Christmas speech was ‘the sadness of separation’.

Today, our troops in Afghanistan, battling valiantly against a lethal and determined enemy in Helmand’s bone-chillingly cold ‘desert of death’, must also overcome the tremendous ordeal of separation from their loved ones: an ordeal that weighs particularly heavily at this time of year.

Under the British Army’s historic regimental system soldiers frequently serve in the same combat unit for many years. They live together, work together, drink together, fight together — and sometimes even get arrested together. Close relationships develop, extending up and down the ranks, making for a tight-knit community: creating the friendships, understanding, trust and loyalty that are essential to effectiveness in war. They become, quite literally, a military family.

The adrenalin-fuelled horrors of violent combat, the like of which our troops experience day in and day out in Helmand, fire this already close comradeship into an iron bond. King George VI, himself decorated for bravery as a gun-turret officer on board HMS Collingwood at the Battle of Jutland in 1916, spelt this out in his 1940 speech: ‘If war brings its separations, it brings new unity also, the unity which comes from common perils and common sufferings willingly shared.’

Last year just before Christmas while attending the funeral of a corporal from my own regiment, killed in Afghanistan, I met a teenage soldier from the same platoon who was home on leave. Surprisingly, despite the death of his friend, he told me how desperate he was to get back to Helmand in time for Christmas. In peacetime most soldiers would, of course, prefer to be with their families at this festive time. But if their mates are in a battle zone, they want to be with them — they need to be with them — sharing their burden and danger.

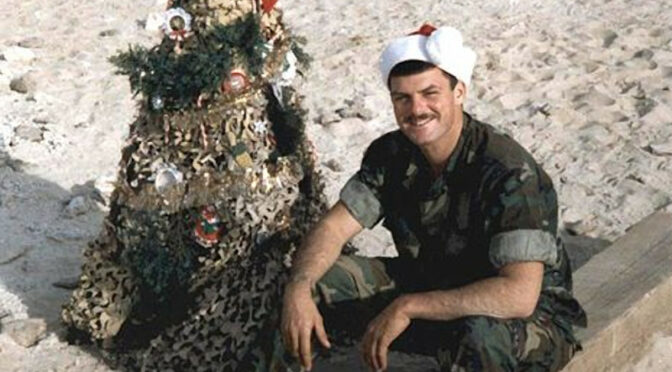

One of the best Christmases I can remember was spent among my fellow soldiers in the desert close to the Iraqi border in 1990 as we prepared to throw Saddam Hussein’s armies out of Kuwait. For me, this elemental desert environment distilled Christmas to its essential simplicity, distancing it from the commercialised event that is now all too familiar.

Many soldiers who would normally eschew religion crowded round the padre’s makeshift desert altar, a sight that became increasingly common as we got closer to the day we expected to fight our way across the border.

At our desert encampment, in keeping with British Army tradition, we officers served roast spuds and turkey to the troops. Afterwards, our commander, determined to give the men some well-deserved respite, ordered that no junior rank would stand duty for the rest of the day. Instead the officers, warrant officers and sergeants manned our sentry positions, radio sets and patrol outposts, washed dishes, scoured pans and, in my case, burnt the contents of the camp latrines.

British squaddies, with the same ingenuity and cunning used to defeat their enemies, will always find a way to bring Christmas cheer even to the most austere and remote of patrol bases. Tomorrow in Afghanistan, Santa hats will appear, tinsel will be conjured up, decorations will be improvised from ration boxes and tin cans, bartered goats will be slaughtered and roasted. It is at this time that our soldiers’ much remarked sense of humour, that most vital component of good morale, will come very much to the fore. In place of carol singing there will be ruthless mickey-taking, endless bickering and heated discussions about football, women and the relative virtues of this year’s X Factor finalists.

Despite all this, there are no days off in a war zone. The famous truce of 1914 when British and German soldiers met in no man’s land to exchange small gifts and play football, and the Northern Ireland campaign, when the IRA traditionally preferred to spend Christmas at the bottle rather than behind the Armalite, were notable exceptions.

In Christmas 2008, our forces launched a major offensive against the Taleban. And, although last year was somewhat quieter, four British soldiers were killed in the week before Christmas and there were several bomb attacks and gun battles on Christmas Day. This year, I expect commanders will try to give the troops some opportunity to relax and to celebrate, but pressure will still have to be kept up on the Taleban, a foe adept at exploiting every opportunity.

This is now the third campaign in which the British Army has fought violent and significant actions over the Christmas period in Afghanistan. In 1842 there was a disastrous retreat from Kabul that ended in the heroic last stand of the Essex Regiment at Gandamack. In 1879 General Roberts heavily defeated an Afghan army at the Siege of Sherpur Cantonment.

The uniquely British regimental system, which has sustained our soldiers during campaigns fought in Afghanistan over more than 150 years, ensures that no soldier is without a ‘family’ at Christmas time. But at quieter moments it is their loved ones at home that come to mind. Paradoxically, our soldiers’ main concern is often that their family’s Christmas will be overshadowed by anxiety about their safety during the tour of duty.

These thoughts were echoed by Sergeant Steven Robinson, of the Yorkshire Regiment, while serving in Helmand last December: ‘This is my second Christmas away out of the last three. And if I’ve learnt one thing, it’s that while it may be tough for us out here, it’s a whole lot harder for those we’ve left behind. Our wives and children are all too aware of the empty seat at the dinner table.’

The concluding words of King George VI’s Christmas message of 1940 could apply as well to our brave and dedicated armed forces on this Christmas Day as they did back then: ‘We do not underrate the dangers and difficulties which confront us still, but we take courage and comfort from the successes which our fighting men and their Allies have won at heavy odds.’

Image: Christmas during Operation Desert Shield/Storm. USMC/Wikimedia Commons