Article published in The Daily Telegraph, 19 December 2024. © Richard Kemp

Is Assad’s fall from power going to lead to the further dismemberment of Syria? What are the wider consequences for the Middle East?

First, it’s important to recognise the true dynamics behind this geopolitical shockwave.

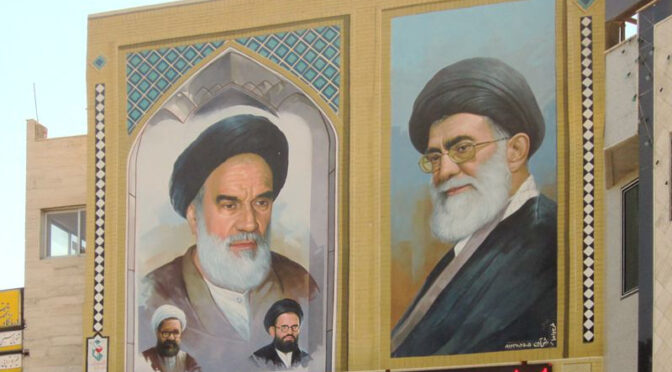

Iran’s supreme leader Ali Khamenei blames the US and Israel for overthrowing Bashar al-Assad. Indeed President Joe Biden has proudly taken credit for what happened in Syria. That’s great for his legacy perhaps, but far from the truth. In reality, Biden tried to obstruct Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s decisive campaign against Iran and its proxies – especially Hezbollah – which was directly responsible for the fall of Assad.

Instead of the US, Israel’s ‘partner’ in ousting Assad was Turkey. Whether there was any coordination between the two we can only speculate, but it was president Racip Erdogan that unleashed Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), which Turkey sponsors with Qatar, to spearhead the drive on Damascus.

The future of Syria is going to be influenced by Israel and Turkey beyond all other forces. The two countries are far from friends, but both have national security interests in Syria. Until Netanyahu ordered the shattering of Syria’s military hardware last week, the country had for decades represented the greatest direct conventional threat to Israel. Courtesy of Assad, Syria was also the principal supply route from Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Unlike Netanyahu, Erdogan has broader designs on the Middle East, including, at least in his mind’s eye, the resurrection of the Ottoman caliphate. He has close ties with Qatar and Sunni jihadist groups in the region, including Hamas and Islamic Jihad, which themselves may now gravitate further towards Ankara as Iran descends: an increasing threat for Israel and many of the Arab countries as his regional power strengthens.

More immediately the 3.5 million Syrian refugees in Turkey are politically problematic for Erdogan and he wants them sent home.

But his highest priority is ending the idea of a Kurdish autonomous region in northern Syria, which he sees as a direct threat to Turkey given the pressures over Kurdish separatism in his own country. There are indications now that Erdogan is winding up for a major assault against the Syrian Kurds.

Significant though they are, the Kurds are just one part of a complex ethno-religious patchwork of rivalry and often deadly antagonism, which includes Sunnis, Shia, Alawites, Druze and Christians. It is unlikely HTS leader Al-Julani will be able to re-unite a long-fractured country any more than Assad could.

Turkey may move to crush the Kurd-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). They will certainly put up a fight, but their future will be more in doubt if President Trump makes good on his apparent intent to withdraw US troops from northern Syria with whom they are allied. The SDF were mainly responsible for the destruction of the Islamic State caliphate in Syria. Fighting against Turkey for their own survival, they would have no capacity against Isis, which could re-emerge more strongly.

Russia – with Iran – kept Assad propped up, but is now in the process of a forced reboot of its strategy in Syria. It seems unlikely Putin will be in a position to help protect his Alawite allies should they come under fire.

Iran has pulled out, but will not have given up on its malevolent designs for Syria despite this catastrophic setback. Tehran has so far avoided direct criticism of HTS and may well be seeking to cultivate a longer term relationship or alternatively shift efforts to destabilise the new government. Neither is beyond the cynical machinations of the ayatollahs.

Beyond Syria itself, what might be the consequences of Assad’s involuntary relocation to Russia?

Islamist opposition groups in Jordan could take inspiration from Julani’s power grab. It’s also possible that HTS and other jihadists in Syria could set their sights on the Hashemite Kingdom. Their goal is the Islamic radicalisation of the Levant. Although perhaps temporarily in abeyance, and with the group fully occupied trying to flex its muscles over Syria, in time that aspiration is likely to return to the fore.

Amman’s problems don’t end there. Iran has long been working to destabilise Jordan and following the loss of Syria that will now become a higher priority. Israel, the US and the UK each have vested interests in Jordan’s stability. Israel in particular has been a life-preserver for the country and is more than ever sharply focused on preventing the downfall of King Abdullah.

While Iran looks to bring down the King, the ayatollahs have themselves just become more vulnerable. One of the major deterrents to uprising against the regime was the unspeakably bloody 14-year civil war in Syria, which cost hundreds of thousands of lives. The opposition in Iran might now become emboldened by a combination of Tehran’s weakness at the hands of Israel and the inspiration of a virtually bloodless revolt in Syria. If the incoming Trump administration frees Israel’s hands to destroy Iran’s nuclear programme in the coming months, that could become the tipping point that results in regime change in Tehran.

Like the fall of Assad, the end of the ayatollahs would be a net gain for Middle East security. But the rise of Erdogan, with his own Islamist agenda, could develop into the next major challenge for this turbulent region.

Image: David Stanley/ Flickr