Article published in The Daily Mail, 22 February 2025. © Richard Kemp

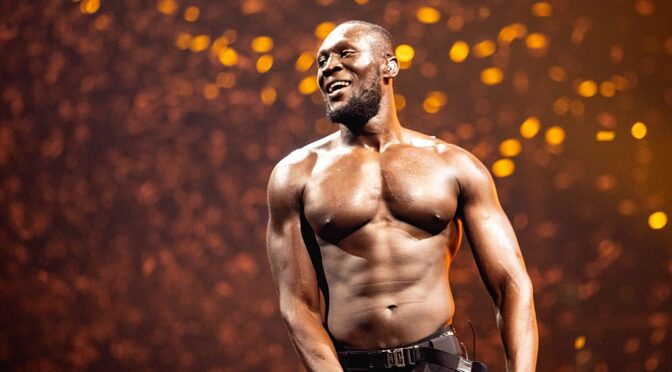

On first impression, the grime rapper Stormzy has little in common with Field Marshal Lord Kitchener.

But should conscription be reintroduced in Britain, it would be the likes of Stormzy, Ed Sheeran and footballing ace Harry Kane tasked with reprising the moustachioed general’s immortal refrain: Your Country Needs You.

Last week, Sir Keir Starmer said he was ‘ready and willing’ to put British boots on the ground in Ukraine. My first reaction was to laugh. Like it or not, our military is on its knees.

Since the end of the Cold War, successive governments have slashed defence spending leaving us with an army that would struggle to defend Dover let alone hold back a Russian advance over the steppes of eastern Europe.

The British Army currently has just over 74,000 full-time personnel of which around just 20,000 are battle-ready soldiers. Russia, on the other hand, boasts close to 1.5 million active soldiers, making it the second-largest fighting force in the world behind its close ally China. Our army is slightly smaller than that of Romania and slightly larger than that of Armenia.

Considering Ukraine shares an unenviable 800 mile-long border with Russia, any Nato force stationed there would need to be formidably large, highly-skilled and ready to combat Russian aggression at a moment’s notice.

Short of discovering a division or two of soldiers behind the sofa, I’m not quite sure what Starmer is thinking. The British Army is already responsible for maintaining a pair of permanent military bases in Cyprus and a garrison in the Falklands, as well as keeping obligations in the Baltics and other parts of the world. That’s before you factor in the need for contingency battalions in case of a domestic emergency.

In short, we can hardly supply more than a couple of thousand troops to any peacekeeping mission in Ukraine. Unless, of course, we expand the size of the army – and fast. It might be a mother’s worst nightmare, but just what would happen if Sir Keir Starmer became the first Prime Minister since the practice ended in 1963 under Harold Macmillan to conscript civilians into the British Army?

Following an emergency Cobra meeting in 10 Downing Street, the Prime Minister – on advice from the defence secretary – would use royal prerogative powers to bypass Parliament and authorise the conscription of civilians into the Armed Forces.

At the same time, emails would go out to the 25,000-strong Army Reserve – some of whom are former servicemen and women – commanding them to report to barracks up and down the country. This email would likely be followed by personal, instructive calls made by regional commanding officers.

The part-time soldiers would have a grace period of between three to five days to take leave from work – as is their legal obligation – and prepare for a tour of duty that would likely last around six months.

In times of crisis, the army frequently calls on its proud bank of reservists, most recently during conflicts in the Balkans and Iraq. But even the reserves would provide insufficient numbers in Ukraine. Therefore back in Whitehall, the Ministry of Defence must decide upon eligibility criteria for conscripts, as well as determining the number required.

Remember, any overseas mission requires at least two distinct forces operating in tandem, with soldiers serving a six-month tour before being relieved for the same period – this is the model deployed in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Nordic countries already employ a form of conscription in the guise of mandatory military service.

According to Finland’s constitution: ‘Every Finnish citizen is obligated to participate or assist in national defence.’ Male school leavers are obliged to serve up to a year learning basic military skills, which they can then call upon if needed later in life.

While citizens can choose between civilian and military service, the punishment for refusing outright both is a hefty six-month jail term. Eighty per cent of men complete their term of service.

Should Keir Starmer need an army at short notice, he would have to perform a precarious balancing act. The greater the number of conscripts to be trained, the more experienced servicemen would have to be withdrawn from duty to do so.

What’s more – as has been well publicised – Britain’s barracks are already overcrowded, run-down and far too few in number to take on vast numbers of conscripts.

The military’s estates team would be urgently tasked with sourcing additional accommodation, classrooms and mess halls. In all likelihood, venues formerly commandeered as Nightingale hospitals during the pandemic – such as the Excel Centre in east London – would be turned into makeshift military barracks.

The next question, of course, is who to call up? When Herbert Asquith’s government introduced conscription in 1916, it applied to all single men aged between 18 and 41.

Currently every role in the British Army is open to both men and women. As a point of political principle, conscription would have to be conducted on a gender-blind basis. Marital status would no longer be considered due to the financial and social independence women enjoy today. And exemptions would have to be made for single parents and carers.

The starting age bracket would be significantly narrower than in 1916, likely from 18 to 30 – of which there are about eight million people.

In Ukraine, the lower limit for conscription is 25 in order to ensure the country still has at least some young men following what has been a devastatingly bloody and prolonged war that has killed – by conservative estimates – up to 80,000 Ukrainians.

Medical checks, meanwhile, will immediately rule out vast swathes of the eight million age-eligible civilians.

As of 2023, the Government estimates that more than 60 per cent of the adult population is overweight – a condition that prevents serving in an active role. For the sake of fairness those suffering from certain self-inflicted conditions, such as obesity, would likely be asked to serve in a separate ‘civilian core’ aiding the war effort domestically in roles such as IT, procurement and logistics.

Chronic illnesses including diabetes, asthma and epilepsy would also rule out potential conscripts. So too would any physical disability including partial blindness, part-body paralysis, scoliosis or amputation. Even those with allergies to foods and medicines would be excused as these can quickly become a liability in the heat of battle or during long, gruelling weeks on the frontline.

The prevalence of mental health issues would also pose a major problem for the MoD. No one should be operating firearms – let alone artillery or tanks – if their mental state makes them a danger to themselves or colleagues.

However, with 5.6 per cent of the British population claiming to suffer with an ‘anxiety disorder’ – of which the number is higher among younger people – no doubt hundreds of thousands of 18 to 30-year-olds would avoid the draft claiming mental health concerns.

The courts – citing the Government’s human rights obligations – would prevent any pushback from the MoD.

Suddenly, that eight million has been halved through medical reasons alone.

Certain key workers will necessarily be excluded. The Government will borrow from pandemic templates to rule which professions are indispensable, settling on key trades such as engineers, electricians, farmers, plumbers and doctors.

While it may not play well politically, the vast majority of those with a criminal record would also be exempt due to the risk they may pose to their fellow servicemen.

Non-Commonwealth citizens are currently not permitted to join the British Army. However, the MoD will likely explore the possibility of adapting this policy in order to call on asylum seekers currently languishing in hotels without purpose or prospect, particularly those who have had experience serving alongside British troops in Afghanistan.

Not only would this be a politically popular move, but provide a fast-track towards gaining citizenship. Of course, for many asylum seekers the inability to speak English and the unwillingess to follow basic commands would make this impossible. And the capacity to accurately vet people’s backgrounds is limited: you simply cannot put a rifle into the hands of someone you know very little about. Think of the many incidents in which Afghan army soldiers deliberately opened fire on their British and American allies.

Eventually, conscripts deemed eligible would be sent a letter to the address listed on the electoral register detailing a time and place to which they must report.

For reasons of morale, a smaller scale version of ‘pals battalions’ could be established in much the same way as they were during World War One, allowing recruits to enlist, train and serve alongside friends and contemporaries.

For the army itself, this is now where the real battle begins. For training 50,000-odd civilians in military discipline and technique is no mean feat. Do not forget, the British Army remains a well-drilled and highly professional fighting force and conscripts would need to be operating at a similar level or risk jeopardising the safety of the entire unit.

A significant number of training bases across the UK have been closed in the past five decades and would likely need to be reopened. I did my own training at Bassingbourn Barracks in Cambridgeshire, a remarkable old facility decommissioned in 2012 but reopened in 2018 as a so-called Mission Ready Training Centre.

It is exactly this kind of vast outdoor location that would be commandeered for the purpose of training new recruits.

It currently takes more than six months to train a recruit, though when I trained in 1977 it took just four. In the case of emergency conscription, training could feasibly be condensed into as little as three months.

In 1916, more than 200,000 people protested against conscription. A generation later, in 1933, an infamous debate between privileged students at Oxford University passed the motion by 275 votes to 153 that: ‘This house will under no circumstances fight for its King and country.’

Though when WWII began, many Oxford students were among the first to enlist. Resistance today, I sense, would be even stronger. For British patriotism has been eroded into near oblivion. When I was a boy in the classroom in the 1970s we were taught of the evils of Empire and the devilish behaviour of our forefathers. This has only got worse.

A poll this month found that only 41 per cent of Gen Z were proud to be British and only 11 per cent were prepared to fight for their country. A further 37 per cent of respondents, all aged between 18 and 27, said they would take up arms only if they ‘agreed with the reasons’.

So how do you convince people to fight for a country they don’t believe in? The Government would engage a number of multimedia and advertising agencies to pump out information across new media platforms including TikTok and Instagram while hiring well-known faces from the worlds of entertainment and sport to spread and share their message.

They would also have to employ thousands of online monitors to take down propaganda and disinformation spread by legions of Russian bots intent on sowing division and misinformation.

When I commanded an undermanned infantry battalion from 1998 to 2001, I sent my soldiers out onto the streets to engage with young people and ultimately encourage them to join us. This tactic was so successful that we ended up with more recruits than we needed.

Without doubt, men in full military regalia walking the streets and engaging members of the public will become commonplace – and a far more likely sight than the ‘press gangs’ bundling errant conscripts into the backs of vans, the like of which we have seen both in Russia and Ukraine. When it comes to convincing someone to risk their life, the carrot always works better than the stick.

Though many people try to tell me that the PlayStation Generation are feckless, idle and lack resilience, I’ve rarely found that to be the case. Every young man or woman who has served under my command has been unfaltering in their commitment to the cause.

I believe today’s young people are capable of the same bravery shown by their forefathers on the beaches of France 80 years ago.

The military is a transformative place, one capable of forging unbreakable friendships and creating men and women of integrity and decency. Serving one’s country is the highest form of valour – and conscription might just be the best thing to happen to this country for a generation.

Image: Wikimedia Commons