How the Nazis murdered 40,000 people in Channel Island concentration camps – and planned to blitz the South Coast with chemical weapons

Article published in The Daily Mail, Saturday 6 May 2017. © Richard Kemp and John Weigold

On a spring afternoon, the grassy headland is bursting with a joy that lifts the soul. Sunshine, blue sea and sky; splashes of golden gorse catch the light and bluebells sway in the breeze; larks float on air currents while gannets in their thousands swoop and screech on a rocky island below.

This is the southern tip of Alderney, smallest of the three main Channel Islands. Across the water, Guernsey, Sark and Jersey glisten. It has to be one of the most beautiful, tranquil and inspiring sights in the whole of Britain.

But close your eyes, take your mind back 75 years . . . and this idyll is a scene of sheer horror.

We are standing on the remains of a massive World War II gun emplacement — a German gun. To the left, a small valley leads down to the cliff top.

All those years ago it was known as the Valley of Death because down it were herded unknown numbers of slave workers, too exhausted to be of use any longer to their Nazi masters, to be thrown to their death on the rocks and swept away by the sea.

Behind us, lost in the undergrowth, are the chilling remains of a concentration camp, run by the SS as ruthlessly and inhumanely as any of its counterparts in the Third Reich, where men were whipped, bludgeoned, starved, hanged, shot, even crucified.

You have to pinch yourself to remember that this is British soil.

Unspeakable atrocities — which we will spell out in detail later — took place here. Not in distant territories on the other side of Europe, but just 60 miles from the coast of England, on an island that is British through and through and has owed its allegiance to the Crown since 1066.

That tiny Alderney — less than four miles long and a mile-and-a-half wide — was the site of slave labour camps during the war has been recognised for decades. But the scale of the operation and the number of deaths there have always been played down. After years of research, we are now in a position to reveal the grimmest truths.

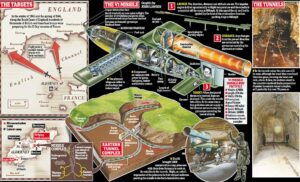

We have uncovered incontrovertible evidence that a top-secret launcher site for V1 missiles — one of Hitler’s vengeance weapons — was being constructed on the island.

And the reason for that secrecy was that, shockingly, they were to be armed not with conventional explosives, but with internationally outlawed chemical warheads, capable of causing the same degree of destruction, terror and panic seen recently by President Assad’s chemical strike in Syria.

They are likely to have contained the very same nerve gas: Sarin.

The target of these deadly doodlebugs? The southern coast of England from Weymouth to Plymouth, where in the winter of 1943 and spring of 1944 hundreds of thousands of British and American troops were assembling and preparing for the D-Day invasion.

If the Alderney missiles had been fired — and our conclusion is that they were within a whisker of this happening — their chemical payloads would have thrown Allied invasion plans into such chaos that D-Day could not have taken place on June 6, 1944, and the whole course of World War II would have been drastically altered.

The Allies would have been on the back foot and Hitler in the ascendancy. He might even have fulfilled his ambition to conquer Britain.

These are startling conclusions and they will change for ever perceptions of what really happened during the German occupation of Alderney.

When the Channel Islands were liberated in 1945, there was a mood and a move to minimise the events of the past five years when a slice of British territory had to exist under the Nazi heel.

It was embarrassing for the British government of the day, which had made a conscious decision in 1940 not to fight for the islands, but leave the residents to their fate.

It was embarrassing, too, for islanders and officials on Jersey and Guernsey who came to terms with the invaders in ways that sometimes bordered on collaboration and even treason. Uncomfortable questions were not asked. Veils were pulled over the truth, with the result that the full story of what happened on Alderney has been hidden.

Until now.

We are military men, with experience from Northern Ireland to Bosnia, the Middle East and beyond. One of us [Col Richard Kemp] commanded British forces in Afghanistan. We have expertise in warfare and weaponry, strategy, logistics, terrain, intelligence.

We have brought that distinctive military perspective to bear on the troubled and often confusing wartime history of Alderney, which we have both known intimately over many years.

We have brought that distinctive military perspective to bear on the troubled and often confusing wartime history of Alderney, which we have both known intimately over many years.

What makes Alderney unique in the occupation of the Channel Islands is that — whereas most of the civilian population remained in Guernsey and Jersey — the island was almost totally evacuated before the all-conquering German army arrived in late June 1940.

In six ships, its 1,500 residents left en masse for the mainland of Britain, where they remained for the rest of the war. Just half-a-dozen resolute souls stayed behind and quietly got on with their lives.

The result was that, with no prying eyes to monitor the activities of the roughly 3,000-strong German garrison, they had a free hand to do whatever they wanted.

They began by putting in massive guns to protect the island from air and sea. Then — on Hitler’s express order in the summer of 1941 after a number of British commando raids on other Channel Islands — they built fortifications on an unprecedented scale to make Alderney virtually impregnable. Forts and barracks built in the Victorian era were updated and strengthened.

New bunkers, blockhouses and reinforced defences were constructed by slave workers brought in their thousands from the Nazi empire all over Europe under the direction of the notorious Organisation Todt.

This was an immense joint civilian and military engineering group that in peacetime had built Germany’s autobahns, and in wartime was given the task of fortifying the defences of the Third Reich.

Hitler made it plain he intended to hang on to the Channel Islands at all costs. He had turned his attention away from Britain after the RAF thwarted his attempt to bomb the country into submission in 1940. He switched the direction of the war to the Soviet Union and the Eastern Front. But his occupation of these outposts in the Channel symbolised his power. They were his jackboot planted firmly in England’s front garden. They would also cover his back.

As his main armies marauded eastwards, the Channel Islands would be a pivotal point of the Atlantic Wall, the line of defences and strongholds he also ordered to be built along the coast of France.

Fortification of Alderney was a brutal business (as we will explain in more detail in the next part of this series on Monday).

When it was completed, the island bristled with hundreds of bunkers, casements and armoured turrets. It had five coastal artillery batteries and 22 anti-aircraft batteries, giving it more cover per square yard than anywhere else in the Third Reich, including Hitler’s Führer Headquarters in Obersalzberg in the Bavarian Alps.

A huge anti-tank wall was built across the island’s most vulnerable landing beach — a concrete installation 15ft high and extending for half a mile, and known by the Russian prisoners who built it as the ‘wall of certain death’ because they died like flies in its construction.

Our military assessment is that all this added up to overkill.

Alderney was massively over-fortified for pure defensive purposes, and inexplicably so. In a post-war report, the German commandant of the Channel Islands, Colonel Graf von Schmettow, disingenuously claimed this was for prestige reasons, because of Hitler’s obsession with making his personal mark on British soil.

But this ignores the reality that Alderney was six times more densely fortified than either of the two main Channel islands, Jersey and Guernsey.

A more likely explanation is that a much more sinister role was intended for the island. Events confirm this.

Shortly after the defences were completed, two odd things happened. Operational German army command of Alderney was switched from St Malo on the French coast — from where the Channel Islands as a whole were run — to a different headquarters in Cherbourg. Alderney was, in effect, being isolated.

Then a brigade of the feared SS arrived in Alderney — and nowhere else in the Channel Islands.

They were the worst of the Nazi butchers, the Fuhrer’s elite storm troopers, who ran the Reich’s chain of concentration and extermination camps incarcerating, torturing and murdering millions of political prisoners, Russian prisoners-of-war and Jews.

They brought 5,000 concentration camp prisoners with them from Germany and took over the Lager Sylt labour camp, which they converted into a permanent high-security camp behind barbed wire — strands of which can still be found — between that beautiful headland we described at the start of this article and what is now the island’s airport.

Why the SS were operating on Alderney is a mystery that has never been satisfactorily explained.

It’s assumed they came simply to back up the Todt operation, but that doesn’t make any sense.

With their black uniforms and chilling death’s head emblem, the SS usually only took on vital or secret tasks; they bypassed the normal military chain of command; they were a law unto themselves.

We know from a surviving German document that the SS commander in Alderney, the monstrous Captain Maximilian List, took his orders directly and personally from its head, Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, the second most powerful figure in the Nazi hierarchy.

So what special, deadly and top-secret task were they pursuing when they came to this dot of an island just 60 miles from the coast of England in March 1943?

We discovered the answer deep underground — in one of the dozen or so tunnels that, as part of their defence plans, the Germans built beneath Alderney (and the other islands), ostensibly as bomb-proof shelters for troops, storage depots and ammunition dumps. And for the first time, the Nazis’ true intent for what they proudly called ‘Adolf Island’ began to emerge.

Water Lane is a leafy track that runs down through a narrow valley known as Le Val Reuters, from the outskirts of St Anne’s, Alderney’s only town, in the direction of the main beach and the harbour. It’s in a high-end part of the island where numerous desirable architect-designed homes have been built in recent years.

Hack through the undergrowth at the side halfway down and you come across the entrance to a tunnel hewn by human hands from the rock. The way in is partly blocked now by earth falls and rubble, and you have to scramble your way up and over and down. But then it opens out in front of you — 10ft wide and 9ft high — stretching out into the distance and the dark.

It’s an eerie place with a doom-laden atmosphere.

The mark of pickaxes and chisels are clearly visible, showing how every inch was clawed out by hand, at what must have been a terrible cost in life and limb.

Underfoot there are the double lines of a railway track, along with pools of mud and water and the rotting remains of wood timbers with which the roof and sides were once lined. There are traces, too, of the waterproof bitumen sheets that completed the lining — an unusual ingredient which, along with the wood, gives us a clue about the history of this place.

Together, they indicate that whatever was stored here was delicate, highly prized and needed an unusually high degree of protection from rock falls and dripping water.

With our military experience, we ruled out the ‘fuel store’ option, which is the accepted view of what this tunnel was for. Nor could it have been for an electricity generating station — another supposed option — because there is inadequate ventilation and the dimensions are all wrong. The tunnel is the wrong size, too, for an ammunition dump — much too small and inaccessible.

But what is most revealing about this tunnel is its strange shape.

We have walked and scrambled our way along its entire length, measured and surveyed every last inch of it, and know that its junctions, unexpected curves and gentle bends do not correspond to the simple, straight lines and efficient use of space we would expect in a conventional military storage tunnel.

What it was intended to house was something way out of the ordinary, something that had to kept on trolleys or trucks and hidden out of sight, to be shunted out when needed.

Drawing on our knowledge of weaponry, things began to add up. The shapes, the length of the curves and the precise measurements suggested that what was to be stored here on those rails was long and thin. Nothing we knew the Germans possessed fitted the bill, apart from a missile.

History, timing and intuition pointed to only one answer to this mystery — the V1, the doodlebug, the prototype for today’s cruise missiles, with which Hitler intended to devastate England.

But that couldn’t be so.

Doodlebug flying bombs — each about the length of a large modern car and with a propulsion engine on top — had wide wings. They would not fit in the Val Reuters tunnel.

Our Eureka moment was when we discovered from technical drawings that those wings were detachable, made of plywood and added to the steel fuselage only just before launch. So, yes, it was possible they were stored here.

There were, of course, scores of verified Nazi V1 sites just a few miles from Alderney, on the Cherbourg peninsula of France and further north in the Pas de Calais.

We visited these and discovered that the measurements of their specially constructed storage facilities corresponded exactly to the shape and dimensions of the Val Reuters tunnel. It couldn’t just be coincidence.

Since German military construction always followed a laid-down template, the evidence was stacking up that we had uncovered a previously unknown V1 launch site — on British soil!

Other bits began to fall into place. Outside the tunnel, at one side of the valley, was a vast embankment of earth and rock that, at first glance, seemed to be no more than the haphazard dumping of spoil from the original excavation. Except that we could see there was nothing haphazard about this at all.

The landscape had been deliberately altered to create a slope leading up from the tunnel’s exit to a specially flattened area with clearance over the surrounding high ground — a perfect site for the 50-metre metal ramps from which V1s were launched.

From an old map, we discovered that there had once been a large water tank here, too, built by the Germans for no apparent reason.

But from our visits to northern France we knew this was a vital feature of every V1 launch site, where copious amounts of water were needed close by so the ramps could be washed down between firings to cleanse them of the chemicals used in the launch process.

All this added up to only one thing: we had undoubtedly uncovered a German missile site.

It was a huge site, too, because the first tunnel was duplicated by the exact same system of underground passages dug out of the rock on the opposite flank of the valley.

We calculated that, between them, they could have housed as many as 72 missiles at any one time.

What came as a shock was that the military high command in Britain had no idea they were here. Through intelligence and overhead reconnaissance, they were aware of V1 preparations in France and did everything in their power to take out the sites and the transport links to them. But the arsenal accumulating on Alderney went totally unnoticed.

Yet a greater shock was still to come.

Our discovery of the true purpose of the Val Reuters tunnels prompted another mystery. Why were the missiles here? Could there be something different and particularly deadly about them?

The Germans had lots of V1 sites on the French mainland capable of hitting the English mainland, constructed without any of the extra difficulty (and labour) of this concealed one on Alderney.

The Germans also had a rule that V1 sites were not to be constructed within range of naval gunfire or where they could be assaulted by commando raids — neither of which conditions were met in Alderney.

There had to be something special going on here, something highly secretive that no one could spy on or detect.

The vital clue was another of the strange features of the Val Reuters tunnel.

At its heart, a quarter of a mile inside the hill, it had two mysterious side tunnels leading off the main track.

Each was about 30 yards long before coming to a dead end. But what was most extraordinary was that their walls and ceilings were rendered with thick concrete (rather than just the standard cement) and finished off to a degree of bone-dry perfection that was hard to comprehend for mere storage areas.

In our investigations, we have seen nothing like these chambers anywhere else in the Channel Islands or northern Europe. What was their purpose? Again, something special had clearly been going on here, but what?

Studying the lie of the land, the logical conclusion we came to was that, on their way to the launch pad, the missiles stored nose-to-tail in the main tunnel were to be wheeled past these chambers. And there, we realised, they would be armed with special warheads. Evidence suggested the contents would be deadly chemicals, specifically the nerve agents Tabun and Sarin, a single droplet of which on the skin can lead to a slow and terrifying death.

The Germans had been developing, weaponising and stockpiling these horrific substances, unknown to Allied intelligence.

One of the very few eyewitnesses to events on Alderney — a fisherman from Guernsey — told British intelligence, most likely in 1943, that a batch of 300 or 400 large, yellow-painted containers had been seen being unloaded from a supply ship in the harbour. Yellow was (and still is) a colour coding for chemical weapons.

He also reported that the German garrison on Alderney had frequent gas drills, often remaining in their masks for a whole day at a time. Even the heads of their horses, but not those of the prisoners, were covered on these occasions.

British intelligence clearly did not cotton on to the significance of this at the time but, for us, everything was checking out.

In our professional military capacities, we are well versed in aspects of chemical weaponry, how it operates and how to counter it.

All those previously unexplained aspects of the Val Reuters tunnel were consistent with the sort of containment and decontamination procedures that surround the use of deadly chemical warheads.

What we are now sure of is that Alderney had a fully developed secret V1 site for missiles loaded with deadly nerve agent.

We can even pinpoint their potential targets. The Val Reuters rock launch ramps — which actually showed up on a British air reconnaissance report from World War II, though their purpose was not recognised — provide flight paths that are precisely aligned to Plymouth and Weymouth.

These were the most important marshalling areas and ports for British and American forces building up for the D-Day invasion of Europe.

We know Hitler planned to cause chaos among the Allied troops, whom the Germans knew were preparing for an assault across the Channel, by launching thousands of V1 missiles armed with conventional explosives from northern France.

This would have been deadly enough, but the extra element of nerve agents raining down from the sky from Alderney, ones that killed with the slightest touch, paralysed and induced fits, would have forced a total re-think.

The invasion plans would have had to be postponed as the Allies sought ways to counter them. The Nazis would have bought themselves valuable extra time, in which more war-winning super-weapons could have been developed.

In the end, Hitler failed to deploy his arsenal of chemical missiles. His V1s in mainland France were not ready to be fired until after D-Day, and they were outflanked by the Allied invasion.

Alderney, too — known as Death Island — did not complete the terrible mission that we believe Hitler and Himmler had it in mind for it.

We can, at least, be thankful for that. But it did live up to its nickname when it came to the fate of the imported slave labourers who built the fortifications, dug the tunnels and constructed the secret missile site.

They died horrible deaths in huge numbers — much higher than have ever been contemplated before, as we will reveal in the next chapter of this chilling story in Monday’s Mail.