Article published in the Colchester Gazette, 10 November 2016. © Richard Kemp

ONE of the most moving letters I have ever read was sent from a young Colchester man to his parents 100 years ago.

“I am writing this letter to you just before going into action tomorrow at dawn,” he began.

“‘I am about to take part in the biggest battle that has been fought in France.”

He went on to explain: “My idea of writing this letter is in case I am one of the costs and get killed. I do not expect to be but such things have happened and are always possible.

“It is impossible to fear death out here when one is no longer an individual but a member of a regiment and of an Army.

“What an insignificant thing the loss of, say, forty years of life is compared with them. It seems scarcely worth talking about.

“Well goodbye, my darlings, try not to worry about it and remember that we shall meet again quite soon.”

He wrote that letter at 8 pm on Friday June 30th, 1916. The next day was the first day of the Battle of the Somme. The British Army suffered by far the greatest casualty rate in its history – 20,000 killed and 40,000 missing or wounded on that one day alone. Among them was the author of that letter, killed as the battle began at dawn.

He had been a pupil at my own school, Colchester Royal Grammar. Two other former pupils and a teacher from there were killed that day. In all, 79 old boys and masters of the school died in the First World War. A remarkable number from a school with only 200 on the roll in 1914.

Many today would dismiss this young man’s sentiments as mere jingoism, claiming after 1914 the initial enthusiasm to defend their country had been extinguished and soldiers were unwilling cannon fodder driven to their deaths by heartless politicians and incompetent generals.

That is to insult their courage and patriotism. When the war broke out, my great uncle, Philip Duncan, was in a reserved occupation which he was not allowed to leave. He spent three years desperately trying to get to the front, finally succeeding in 1917, in the full knowledge of the slaughter on the Somme, at Flanders and in the clouds of poison gas at Ypres. Three weeks after arriving at the front he was killed leading his men in the mud of Passchendaele. A fate he knew he was almost certain to meet.

As we remember our war dead on Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday this year it is worth taking a moment to reflect on the meaning of the sacrifice made by men such as the grammar school pupils who fell on the Somme and my own great uncle.

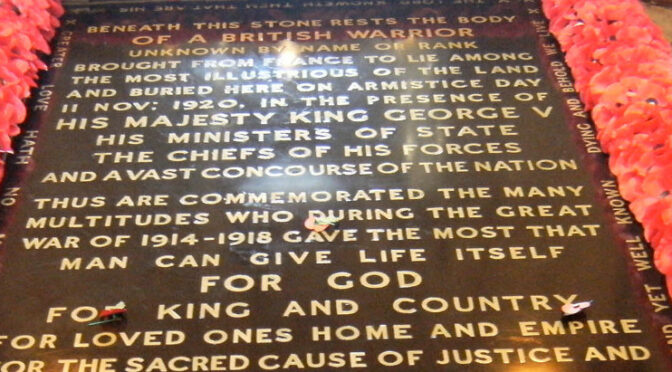

The inscription on the Tomb of The Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey includes these words:

Thus are commemorated the many multitudes who during the Great War of 1914-1918 gave the most that man can give: life itself.

Their contribution was greater than anyone else could ever make: even the most inspiring leader, the finest scholarly mind, the greatest captain of industry, the most munificent benefactor. All that they had they gave, all that they might have had, all that they had ever been, all that they might ever have become.

They forfeited every hope and every dream, every laugh, every tear. Every tender moment with the girl they married or might have married. Every smile from a beloved son or daughter, every fatherly cuddle, every beer enjoyed with friends, every game of football played and watched. Every song, every dance, every joyful holiday. The exhilaration of every achievement, the frustration of every setback, the sorrow of every failure.

Such selfless dedication to duty was common among that generation. The famous headmaster of Colchester Royal Grammar School at the time, Percy Shaw Jeffrey, commented: “I cannot tell you with what humble pride and satisfaction we have seen the rush of our old boys to the colours.’”

The same spirit remains common today. The peak of Army recruiting in recent years was at a time when the campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq were at their bloodiest.

There are those that believe modern youth lacks the patriotism, sense of duty, hardiness and courage of previous generations. This is nothing new. Even back in 1915, Shaw Jeffrey commented: “We were always told school boys nowadays were of a decadent type, and that better manners showed a softer fibre.”

As he observed, the unequalled performance of the British Army in the Great War disproved this. My own experience leading men in battle, including many Colchester men, has shown me the same thing. Those who fought and died in the Great War would have been immensely proud of the fighting spirit, valour and dedication of their young successors in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Speaking of the fighting men our town was producing back then, Shaw Jeffrey said: “The British soldier has shown his quality, and in Colchester they might well say they had been living for years among heroes and never knew it.”

Today we can be both grateful and proud here, as in the country as a whole, there have been and continue to be brave men and women who are willing to give up their own life that others might live in freedom.

Image: Wikimedia Commons