Article published in The Daily Telegraph, 13 June 2025. © Richard Kemp

When I was woken up this morning at 3am by sirens that sounded across Israel I knew exactly what was happening. Now the sirens are sounding here again as Iran attempts to retaliate against Israel’s deadly, effective strikes against its nuclear weapons enterprise.

But the signs had been piling up for the last few days: International Atomic Energy Agency declaring Iran in breach of its obligations, US pulling non-essential staff out of embassies, hospitals in Israel made ready, a warning issued to Hezbollah in Lebanon against attacking; the list goes on. But the signs of the inevitable had also been there for many years before.

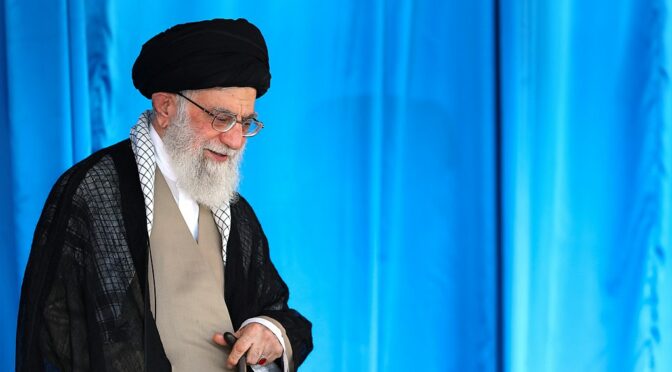

Iran has been a rogue state since the ayatollahs seized power in 1979. The Islamic Revolution that year was built on ‘death to Israel’ and ‘death to America’. The US was the ‘Great Satan’, Israel and Britain the ‘Little Satans’. These were not mere words. Iran was behind the suicide bombings that killed 241 US and 58 French military personnel plus six civilians in Beirut in 1983, as well as 63 deaths at the US Embassy there six months before.

Iran’s dirty work was also responsible for the killing of 85 people at a Jewish community centre in Buenos Aires in 1994, as well as 29 in an attack on the Israeli embassy in the same city in 1992. Iran and its proxies killed at least 1,100 British, American and allied troops in Iraq between 2003 and 2007 as well as an unknown number of coalition troops during the Afghanistan campaign. They have targeted US bases, international shipping and oil fields in Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

And they have been attacking and killing Israeli soldiers and civilians for decades. That eventually culminated in the October 7 pogrom in Israel, in which 1,200 people were killed and many were taken hostage. There is much more to add to Iran’s catalogue of terror: a bomb factory in London, for instance, that was disrupted by British security services in 2015 and alleged attempted terrorist attacks in the UK leading to arrests last month. Iran has also been the major supplier of drones and missiles to Russia which have been used against civilian and military targets in Ukraine.

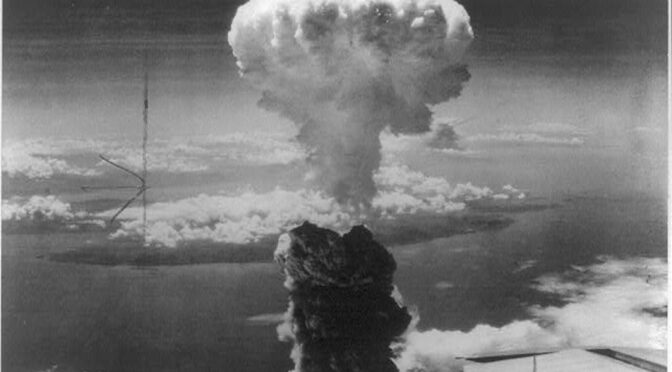

For decades the Tehran regime has been working to develop nuclear weapons. Although Iran sometimes paused its programme when it feared punitive action from either the US or Israel, it has refused to stop; its upward trajectory has now reached a point where the IAEA believes it now has enough highly enriched uranium to make at least ten bombs.

Iran’s ballistic missile capability has also been proceeding apace, giving it a nuclear capability to span the region, and of course there are also other more covert means of delivering nuclear weapons. Until recently the missing part of the intelligence jigsaw was weaponisation, the ability to turn fissile material into a viable bomb. Today Israeli prime minister Netanyahu revealed that Iran has indeed been working on that important final step.

With all diplomatic pathways to prevent Iran becoming a nuclear armed state closed off, Israel had no choice but to attack. The alternative would have been unthinkable: a regime that has repeatedly proven its capacity for unlimited violence acquiring nuclear weapons capability.

But Iran’s dictators are now in a desperate situation. Israel has decapitated their armed forces and destroyed significant parts of their offensive capability. The IDF will continue to attack Iran’s nuclear facilities and to degrade its capacity to strike, although we don’t yet know whether it will be completely neutralised.

If not, like Hitler in his bunker, the unhinged ayatollahs might try to lash out at oil states in the region – either with their own remaining armoury and or using what terrorist proxies remain to them. They might even attack US bases in the Middle East, which they have threatened to do, even though they know that could bring about their Armageddon.

All of that might lead to insurrection in the country. Much of the population in recent years has reached new heights of hatred for rulers that have oppressed, imprisoned, tortured, murdered and impoverished them. But it is far from clear that there is a viable opposition able to step up; one scenario is perhaps some kind of military coup.

Until then Iran and Israel will trade blows: but my money is on Israel talking less and hitting harder.