A version of this article was published in The Daily Express on 2 November 2020. © Richard Kemp

The first Remembrance event was in 1919, as the worst pandemic suffered by Britain in modern times, killing 228,000 Britons, subsided. Nothing would deter our forbears, who had also just endured the most devastating conflict this country has ever known, with nearly a million dead, from commemorating those who gave their all.

How did Hitler’s war, with its vicious aerial bombing in London and across much of the country, affect those who wished to commemorate the fallen? They didn’t think of cancelling Remembrance, even as thousands were killed and wounded and whole streets of houses were laid waste by Nazi bombs. Instead they held their heads high and conceded only to move it to Sunday to minimise impact on war production.

Their message to us is clear: don’t let Covid kill Remembrance Sunday.

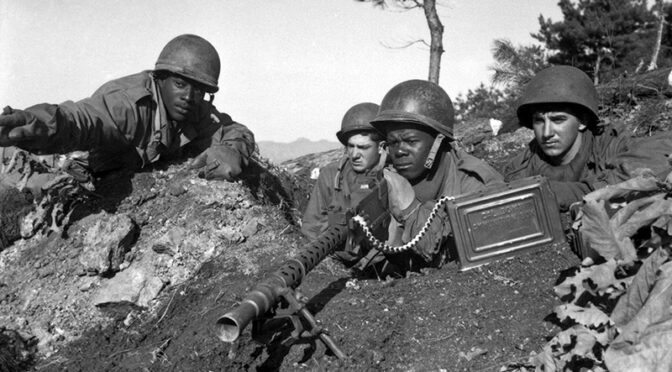

We owe our freedom and our very way of life to those who gave everything they ever had or would ever have, whether in Helmand, Basra, Belfast, at Imjin, Kohima, Normandy, Alamein, Dunkirk, in the Atlantic and the Pacific, on the Somme, at Ypres or any of the hundreds of battlefields across the world where British forces fought and died for us.

This week in 1917, the horrific Battle of Passchendaele was raging. My great uncle, 2nd Lieutenant Philip Duncan, was killed there, having twisted the rules to get into the fight for his country’s life. On Remembrance Sunday I shall remember him and the thousands of other British troops that died in the mud alongside him.

This Remembrance Sunday we must hold parades and ceremonies at our war memorials across the country as we have done for over a Continue reading