Article published by the Gatestone Institute, 4 September 2022. © Richard Kemp

Fifty years ago this week, 5th and 6th September 1972, the world watched in horror as Jews were again brutally murdered on German soil, at the Olympics in Munich. Eight Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) terrorists, using the cover name “Black September,” tortured and murdered 11 Israeli athletes, emasculating one of them as he lay dying in front of his team-mates. They stormed the athletes’ accommodation, killed two immediately and held the remainder hostage, demanding the release of 234 terrorist prisoners held by Israel. Prime Minister Golda Meir — who had been a signatory to Israel’s declaration of independence in 1948 — refused to bargain with them, branding it blackmail. She later said: ‘We have learnt the bitter lesson. One may save a life immediately only to endanger more lives. Terrorism has to be wiped out.’

Meanwhile Berlin offered safe passage and unlimited cash to the terrorists, which they turned down. In the chaos of a disastrously botched German attempt to ambush the killers at the Fürstenfeldbruck airbase near Munich on 6th September, with hand grenades and bullets the terrorists butchered the remaining nine athletes in the helicopters that brought them there, as well as a German policeman. All but three of the terrorists were killed in the firefight. The IDF special forces unit Sayeret Matkal (General Staff Reconnaissance Unit) had been poised to mount a rescue operation, but the German government refused to allow them into the country and hubristically rejected advice from the chiefs of Mossad and Shin Bet who had flown in.

They were forced to stand and watch as their fellow Israelis were slaughtered.

The terrorists were armed with weapons smuggled into Germany via diplomats from Libya, where they had been trained for their murderous mission. Libyan president Muammar Gadaffi had funded the attack at the behest of PLO leader Yasser Arafat, who subsequently denied any involvement and two years later was feted in a standing ovation at the United Nations General Assembly. Mahmoud Abbas, now president of the Palestinian Authority, was a key player in preparing the operation. As he flaunts himself on the world stage 50 years later, Abbas still refuses to express any remorse for the murders he helped bring about.

Even as the attack unfolded, Avery Brundage, chairman of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), insisted that the games must go on. While two Israelis lay dead and nine were held at gunpoint, the first athletics event of the day began on schedule, with German precision, at 8.15 am. Brundage only agreed to a suspension 12 hours after the assault began, and following a brief pause, the sports proceeded as though nothing had happened. ‘Incredibly, they’re going on with it,’ the Los Angeles Times wrote at the time, ‘it’s almost like having a dance at Dachau’ (which was just a few miles away).

Addressing a memorial service the day after the murders, Brundage, who had successfully fought against a US boycott of the Nazi Berlin Olympics in 1936 over persecution of Jews, outrageously belittled the murder of the 11 Israelis. A request by the German chancellor to half-mast national flags at the games was rescinded after Arab countries refused to comply.

The chief of Mossad, Zvi Zamir, who witnessed the massacre, wrote:

‘We watched the Israeli athletes, with their hands tied, flanked by the terrorists, and all in step they marched toward the helicopters. It was an appalling sight, especially to a Jew on German soil.’

Violent action against the PLO followed swiftly. Two days after the massacre, on 8th September, Israeli warplanes bombed ten PLO bases in Syria and Lebanon, killing up to 200 terrorists and bringing down three Syrian jets that tried to intercept the strike force. This was followed by a ground operation, with IDF armour entering Lebanon and killing an estimated 45 PLO terrorists.

A resolution at the UN Security Council on 10th September calling on Israel to halt its military operations in Syria and Lebanon, while pointedly making no mention of the Munich massacre, was vetoed by the US against strong protests from the Soviet Union and China. The Soviet ambassador remarked that putting the Israeli raids on the same footing as the events in Munich ‘would be condoning the aggressive policy of the Israeli maniacs’. Of course the Soviet Union itself had blood on its hands at Munich, having created the PLO and set it on the path to terrorism in Europe, funding and supporting attacks.

US ambassador to the UN, George H.W. Bush, said the resolution ignored realities and ‘looked to effect not cause’. He went on to say its ‘silence on the disaster in Munich’ invited more terrorism. Addressing the wider issue of Palestinian violence, he added: ‘We seek and support a world in which athletes need not fear assassins and passengers on planes need not fear hijacking.’

Bush’s words in New York were well received in Israel, but words were not enough for a traumatised nation that had just witnessed 11 coffins leaving Lod airport in a fleet of IDF command cars, and whose distress had been heightened by the decision to continue with the games, as though the massacre of Jews in Europe could again be simply brushed aside. It fell to Golda Meir to convert Bush’s words into action: it was her people who were in the cross-hairs.

For that, the military raids in Syria and Lebanon were not sufficient. Dealing with the threat from countries in the Middle East was one thing, confronting terror in Europe something quite different. Before Munich, Israeli intelligence had repeatedly given European governments information about terrorist cells and attack plans in their countries. But as Meir told the Knesset foreign affairs committee: ‘We inform them of it once, twice, three times or five times, and nothing happens.’ [Quoted in Rise and Kill First, Ronen Bergman, 2018] European reluctance to act on intelligence and antagonise Palestinian terrorists and their Arab sponsors had permitted a wave of deadly attacks. In the previous three years, 16 people had been killed and wounded in seven terrorist assaults against Israeli and Jewish targets in West Germany alone.

Faced with inaction in Europe, the Mossad had previously proposed direct attacks against terrorists on the continent. Meir, committed to respecting the sovereignty of friendly countries, refused and authorised action only in Middle Eastern nations that were hostile to Israel. That all changed with Munich. Six days after the massacre she told the Knesset:

‘At any place where a plot is being laid, where they are preparing people to murder Jews, Israelis — Jews anywhere — it is there we are committed to striking them.’ [Rise and Kill First, Ronen Bergman, 2018]

With those words, Meir launched one of the most successful counter terrorist operations the world has ever seen.

Despite this tough stance, before putting her decision to the cabinet, Meir had understandably agonised, both on moral and political grounds. She later said:

‘There’s no difference between one’s killing and making decisions that will send others to kill. It’s exactly the same thing, or even worse.’

She was also concerned about the young Israelis she would be sending into the gravest physical and psychological danger. She knew that if a man can hunt, he can also be hunted. As she put it: ‘They sit right in the jaws of the enemy.’

The Mossad had been preparing for such an operation since 1969 and immediately dispatched targeted killing teams, codenamed ‘Bayonet’, into Europe. The first of several strikes came less than two months after Munich, on 16th October in Rome, when the PLO representative in Italy, Wael Zwaiter, a cousin of Yasser Arafat, was gunned down. Further killings followed in France, Cyprus, Greece and elsewhere. Executions were suspended after July 1973, when an innocent man, mistaken for a PLO terrorist, was killed in Lillehammer, Norway. They resumed in 1978 under Prime Minister Menachem Begin.

Beyond Europe, on 9th April 1973, Operation Spring of Youth, a joint IDF-Mossad raid in Beirut led by Ehud Barak (who later became prime minister), killed three senior PLO leaders and around 50 other terrorists. The next day, Walter Nowak, German ambassador in Beirut, condemned the assault. Scandalously, just six months after Munich, he had been meeting with one of the Black September leaders killed in the IDF raid, Abu Youssef, himself an organiser of the massacre, to offer the prospect of creating ‘a new basis of trust’ between the PLO and the German government. This incident characterises the two approaches: as Germany was appeasing the terrorists, Israel was eliminating them.

The targeted killings ordered by Golda Meir were intended to stop terrorist attacks against Israelis being conducted in and from Europe and not, as is often supposed, in revenge for Munich — most of those killed were not directly connected to the Olympics massacre. Mossad Chief Zvi Zamir makes clear: ‘We were not engaged in vengeance.’ He goes on to explain: ‘What we did was to concretely prevent in the future. We acted against those who thought that they would continue to perpetrate acts of terror.’

This was about pre-emption and disruption of terrorist attacks against Israeli citizens in countries where the national authorities had shown themselves unwilling to act. It was also about deterrence, making terrorists understand that the price of their actions would be high — preferably too high. That accounted for the dramatic way some of the attacks were conducted, including the use of explosives rather than more clinical means or incidents that could be passed off as accidents. The Mossad wanted the terrorists to have no doubt why their comrades were being killed and who was doing it. For political reasons, this had to be balanced against plausible deniability, a consistent principle of many Israeli counter-terrorist operations before and since. That went badly wrong at Lillehammer, where six Mossad operatives were arrested and put on trial.

The imperative for Israel’s targeted killings was again confirmed less than two months after the Olympics, when a Lufthansa flight from Beirut to Frankfurt was hijacked by Palestinians demanding the release of the three terrorists who had survived in Munich. The German government immediately paid a $9 million ransom and released the men, who were flown via Zagreb to Libya, where they received a hero’s welcome.

The last thing Berlin had wanted was to put these murderers on trial, with German intelligence warning of further acts of terrorism to force their release. This turn of events therefore was highly convenient and some experts, including the chief of Mossad at the time, have accused the German government of paying the PLO to stage the hijacking to give cover for release of the terrorists. That version was also confirmed in an interview with the self-confessed leader of the Munich massacre, Abu Daoud.

After they were freed, the head of the German foreign ministry wrote a memo to the chancellor’s office saying: ‘We should be pleased that the whole thing has calmed down sufficiently.’ That reflected a prevalent attitude across Europe then and later. In 1977, French authorities arrested Abu Daoud, the terrorist leader. They asked whether Germany wanted him extradited but the Germans declined. The French government, worried about the potential for attacks on their own soil as a result of holding him, allowed Daoud to fly to Algeria a few days later in the face of strong protests from Israel and the US and praise from the Soviet Union. Until his death, he boasted about the massacre he had organised.

As well as fear of terrorism, the appeasement of Arab terrorists by European governments was motivated by worries that too close an alignment with Israel on security would harm their relations with Arab countries, jeopardising oil supply and export contracts.

American and European leaders were often critical of Israel’s targeted killing policy, sometimes affecting intelligence sharing as well as diplomatic and trade relations, and with some accusing Israel of terrorist tactics. As Golda Meir pointed out:

‘The person who threatens with a gun and the person who defends himself in order to ensure that the gun is not fired at him are not the same.’

After Islamic terrorists started turning their guns on Western citizens, these ‘principled’ objections necessarily dissolved, with America and its allies frequently forced to resort to a policy modelled on Israel’s. The US and Britain used intelligence agencies, special forces, drones and airstrikes to carry out targeted killings of terrorists including in Yemen, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria. Two days after the 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, French armed forces, supported by Britain, launched a wave of airstrikes against Islamic State bases in Syria, echoing Israel’s attacks in Lebanon and Syria in the days after Munich.

Unsurprisingly, in this changed situation, whenever the Mossad provided European countries with intelligence about terrorist plans on their soil they did not have to be told ‘twice, three times or five times’. With their own citizens now in the cross-hairs, they quickly took the action they failed to take in the 1970s when Israelis were the main target.

Too often Western nations, despite earlier rejection, condemnation and sometimes hostility, have eventually been obliged to follow the lead Israel was first forced to take to protect its people. American and European responses to jihadist attacks on their own territory, especially after 9/11, is an example of that.

We are at present living through another example: the Iranian nuclear threat. Israeli leaders have repeatedly warned that Tehran’s nuclear programme not only represents grave danger to their own country but to the entire region and to the world. As in its response to Munich, Israel is conducting a covert campaign to stop it, including by targeted assassinations. Meanwhile the US and European countries are appeasing the mullahs in Tehran, just as they did with Palestinian terrorists in the 1970s, and are on the verge of striking a deal that will pave the path to an Iranian nuclear capability. This time, ignoring Israeli warnings will have even more dire and far-reaching consequences.

Israel’s vigorous campaign after Munich was a success. It persuaded the Arab world that the Mossad could strike wherever and whenever it liked, instilling fear into the terrorists and forcing them to run and hide in places where they had previously operated with impunity, and some moderate Arab governments even pressured the PLO to halt their attacks. The offensive did not end all Arab terrorism in Europe against Israelis, and as with counter-terrorist activities everywhere, there were some seriously adverse consequences. But the Mossad’s actions on the continent and Operation Spring of Youth in Beirut convinced PLO leader Yasser Arafat to order an end to Black September attacks on targets outside Israel by the end of 1973. As Meir said:

‘We don’t thrive on military acts. We do them because we have to, and thank God we are efficient.’

Munich is sometimes thought of as Israel’s 9/11. Fifty years on, the trauma of the 1972 massacre remains etched deep into the minds of every Israeli and of many beyond who had watched it unfold with heart-breaking anguish. No doubt the 11 Israelis who perished at Munich were uppermost in the minds of those brave men and women who played their individual parts in the campaign that aimed to prevent a repetition of the horrors the athletes had faced. In Golda Meir’s words at the time:

‘Perhaps the day will come when the stories of heroism and resourcefulness, sacrifice and devotion, of these warriors will be told in Israel, and generations will recount them to those who follow them with admiration and pride, as yet another chapter in the heritage of heroism of our nation.’

In memory of:

David Berger

Anton Fliegerbauer

Ze’ev Friedman

Yosef Gutfreund

Eliezer Halfin

Yosef Romano

Amitzur Shapira

Kehat Shorr

Mark Slavin

Andre Spitzer

Yakov Springer

Moshe Weinberg

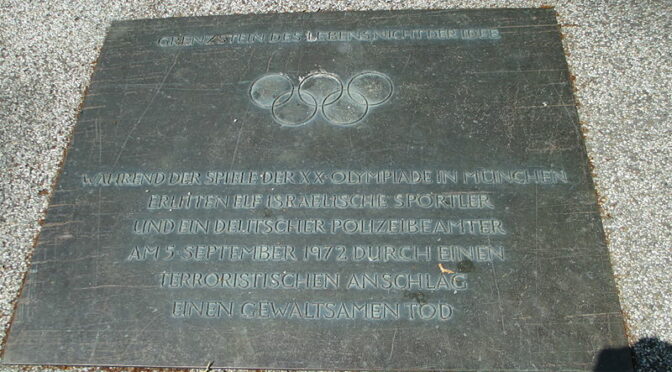

Image: Munich massacre memorial in Munich. Source: Wikimedia Commons